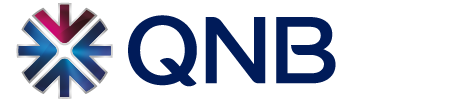

Productivity growth is the single most important driver of long-term economic prosperity. It determines how fast an economy can grow without generating inflation, how quickly living standards improve, and how sustainably wages can rise. Yet for much of the post-World War II period, productivity growth has been volatile in the US, with long periods of high growth followed by long periods of low growth. After averaging close to 3% per year in the post-war decades, labour productivity growth slowed markedly until the wave of internet innovation and e-commerce in the mid-1990s and early 2000s. Following the Global Financial Crisis that started in 2007 until the pre-pandemic period, productivity remained weak. The post-pandemic recovery may have ignited the early phase of a new wave of innovations, led by artificial intelligence (AI).

Several structural forces help explain why productivity growth became harder in countries that are high income and are at the frontier of technological advancements. As economies mature, the most transformative innovations tend to plateau after a period of high productivity, losing momentum rapidly in the absence of additional technological breakthroughs. In this context, many economists argue that “ideas are getting harder to find,” meaning that increasingly larger research efforts are required to achieve the same growth impact as in the past. At the same time, the pace of educational penetration has plateaued in advanced economies, limiting gains from human capital accumulation as most of the working population already present high education levels. Together, these forces contribute to a phase of subdued productivity growth, constraining potential GDP and reinforcing the idea that advanced economies had entered a low-growth equilibrium.

However, this narrative is now being fundamentally challenged by the emergence of AI as a new potential technological revolution, following the breakthrough of generative AI since the launch of ChatGPT in 2020-22. After a few years of more massive investments in AI, it is now adequate to consider whether AI will be able to stop the low productivity phase.

In our view, two main factors support the promise of AI as a significant engine for US productivity and growth.

First, the unique nature of AI suggests a sustained period of accelerated productivity ahead of us. Unlike prior waves of digitalization that primarily enhanced communication, data storage, and process automation, AI represents a distinct and potentially far more powerful class of technology. At its core, AI is not merely a tool for efficiency but a system capable of generating new knowledge, identifying patterns at superhuman scale, and accelerating problem-solving across virtually every sector of the economy. This characteristic gives AI the potential to act as a true “general-purpose technology,” similar in scope to electricity, the internal combustion engine, or the internet.

By augmenting cognitive labour, AI extends the effective frontier of human intelligence. It compresses research timelines, speeds up design and engineering, enhances medical diagnostics, improves logistics optimization, and enables real time strategic decision making. Crucially, AI does not only reduce costs; it also expands the range of what is economically and technically feasible. Ad extremum, AI also introduces the possibility, previously inconceivable in conventional economics, of partially relaxing the classical constraints of scarcity itself. By radically augmenting cognitive labour and enhancing the productivity of capital, AI could make economic output become less tightly tethered to the physical expansion of workers and machines. In this sense, AI is not just a productivity enhancing tool but a productivity-creating engine, with the potential to lift both the level and the growth rate of output over time.

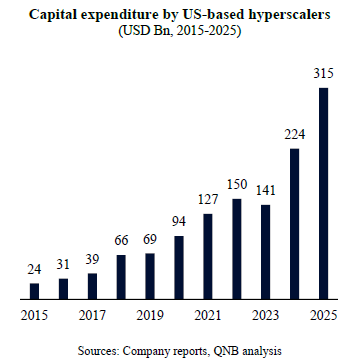

Second, AI is already producing an extraordinary cycle of large scale capital expenditures (CAPEX) in the US. US hyperscalers, led by firms such as Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta, are deploying unprecedented levels of capital into AI-related infrastructure, including data centres, advanced semiconductors, high bandwidth networks, and specialised computing architectures. Importantly, these companies are among the most efficient capital allocators in corporate history, with long track records of disciplined investment and value creation. Their collective decision to commit hundreds of billions of dollars to AI is therefore a powerful market signal. It reflects not speculative enthusiasm, but a high conviction assessment that AI will fundamentally reshape production functions across the economy.

These investment dynamics also matter for macroeconomic transmission. Large scale capital deepening raises the amount of productive capital per worker, directly lifting labour productivity. Moreover, AI-related infrastructure has strong network effects: once the core platforms are in place, adoption across firms and sectors can accelerate rapidly. This creates the conditions for multi-year diffusion cycles, rather than short lived productivity spikes. In effect, the US economy seems to be currently building the physical backbone for a new growth regime over the coming years.

All in all, after a long period in which productivity appeared trapped by structural headwinds, the US now stands on the threshold of a potentially powerful new growth cycle. Importantly, these gains are likely to spread quickly to other countries, particularly Asian and Middle Eastern economies that are investing heavily across the AI supply chain. AI adoption is also likely to be global due to the relatively low cost of accessing the benefits and outputs of AI. Taken together, this should provide a comfortable support to uplift global growth.

Download the PDF version of this weekly commentary in English or عربي